Attention? Attention!

Back HomeSource : Lilian

- What’s Wrong with Seq2Seq Model?

- Born for Translation

- A Family of Attention Mechanisms

- Neural Turing Machines

- Pointer Network

- Transformer

- SNAIL

- Self-Attention GAN

- References

Attention has been a fairly popular concept and a useful tool in the deep learning community in recent years. In this post, we are gonna look into how attention was invented, and various attention mechanisms and models, such as transformer and SNAIL.

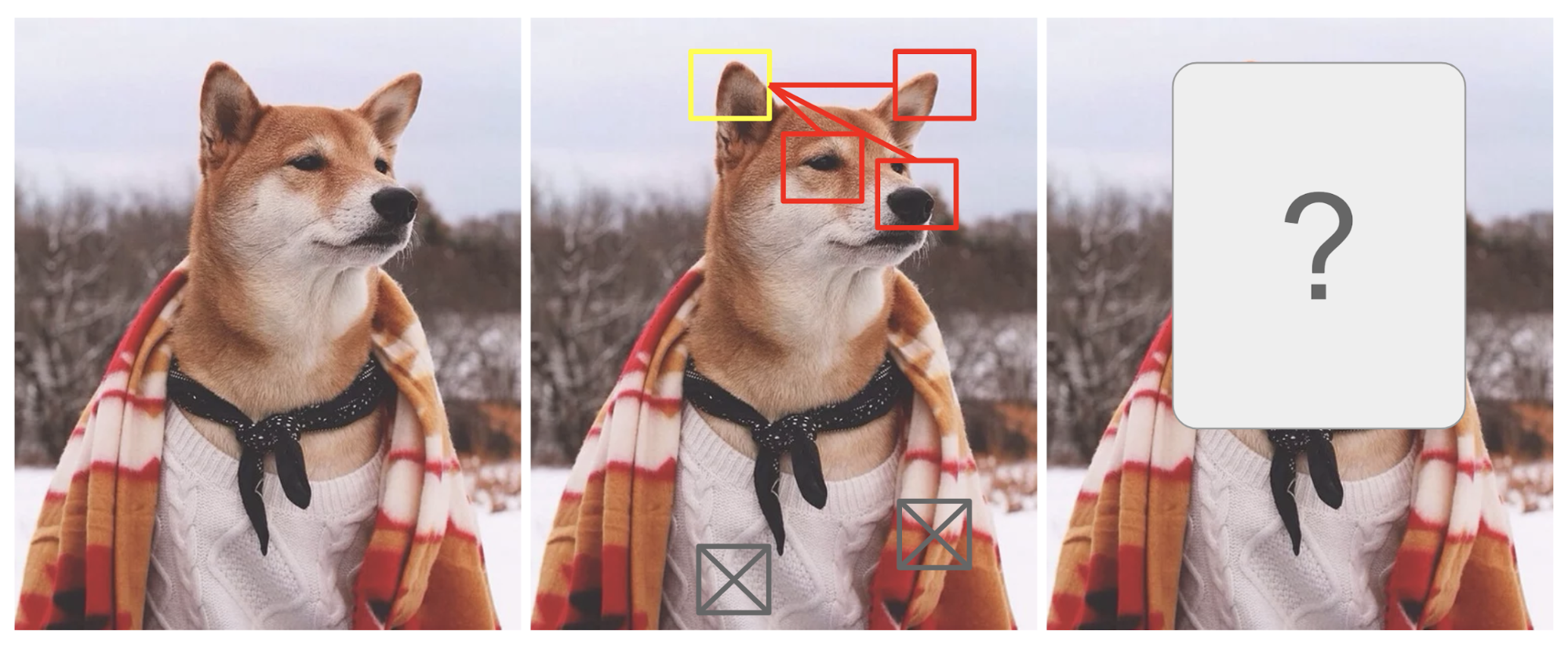

Attention is, to some extent, motivated by how we pay visual attention to different regions of an image or correlate words in one sentence. Take the picture of a Shiba Inu in Fig. 1 as an example.

Fig. 1. A Shiba Inu in a men’s outfit. The credit of the original photo goes to Instagram @mensweardog.

Human visual attention allows us to focus on a certain region with “high resolution” (i.e. look at the pointy ear in the yellow box) while perceiving the surrounding image in “low resolution” (i.e. now how about the snowy background and the outfit?), and then adjust the focal point or do the inference accordingly. Given a small patch of an image, pixels in the rest provide clues what should be displayed there. We expect to see a pointy ear in the yellow box because we have seen a dog’s nose, another pointy ear on the right, and Shiba’s mystery eyes (stuff in the red boxes). However, the sweater and blanket at the bottom would not be as helpful as those doggy features.

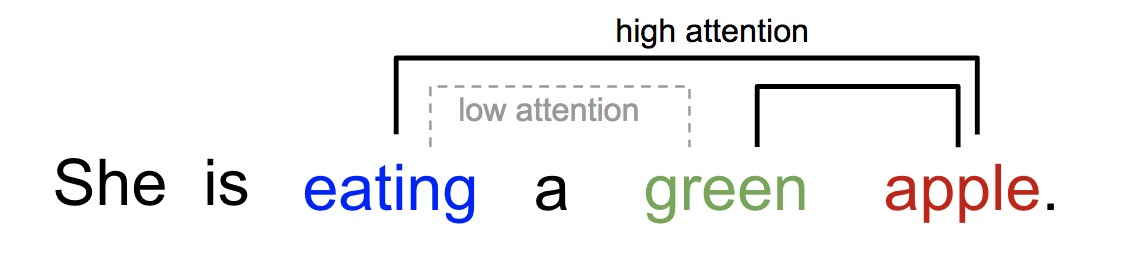

Similarly, we can explain the relationship between words in one sentence or close context. When we see “eating”, we expect to encounter a food word very soon. The color term describes the food, but probably not so much with “eating” directly.

Fig. 2. One word “attends” to other words in the same sentence differently.

In a nutshell, attention in deep learning can be broadly interpreted as a vector of importance weights: in order to predict or infer one element, such as a pixel in an image or a word in a sentence, we estimate using the attention vector how strongly it is correlated with (or “attends to” as you may have read in many papers) other elements and take the sum of their values weighted by the attention vector as the approximation of the target.

What’s Wrong with Seq2Seq Model?

The seq2seq model was born in the field of language modeling (Sutskever, et al. 2014). Broadly speaking, it aims to transform an input sequence (source) to a new one (target) and both sequences can be of arbitrary lengths. Examples of transformation tasks include machine translation between multiple languages in either text or audio, question-answer dialog generation, or even parsing sentences into grammar trees.

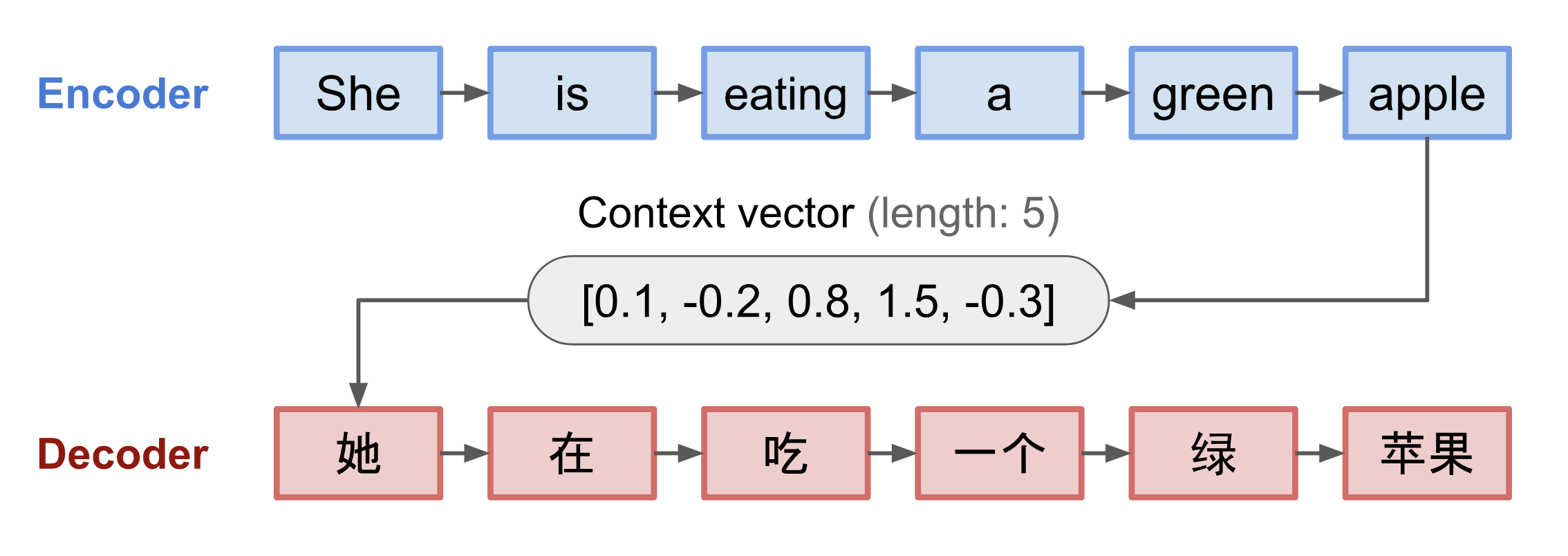

The seq2seq model normally has an encoder-decoder architecture, composed of:

- An encoder processes the input sequence and compresses the information into a context vector (also known as sentence embedding or “thought” vector) of a fixed length. This representation is expected to be a good summary of the meaning of the whole source sequence.

- A decoder is initialized with the context vector to emit the transformed output. The early work only used the last state of the encoder network as the decoder initial state.

Both the encoder and decoder are recurrent neural networks, i.e. using LSTM or GRU units.

Fig. 3. The encoder-decoder model, translating the sentence “she is eating a green apple” to Chinese. The visualization of both encoder and decoder is unrolled in time.

A critical and apparent disadvantage of this fixed-length context vector design is incapability of remembering long sentences. Often it has forgotten the first part once it completes processing the whole input. The attention mechanism was born (Bahdanau et al., 2015) to resolve this problem.

Born for Translation

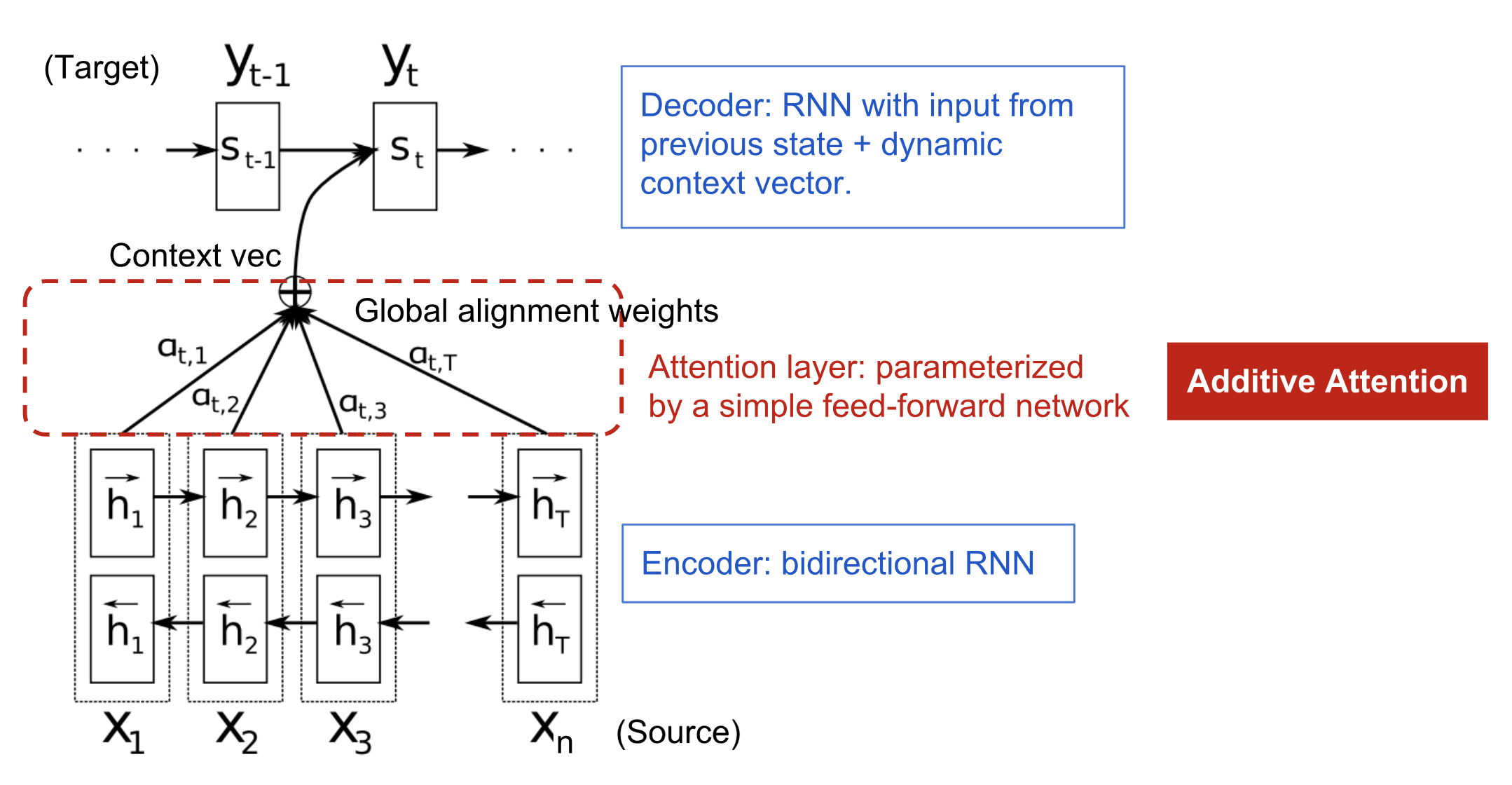

The attention mechanism was born to help memorize long source sentences in neural machine translation (NMT). Rather than building a single context vector out of the encoder’s last hidden state, the secret sauce invented by attention is to create shortcuts between the context vector and the entire source input. The weights of these shortcut connections are customizable for each output element.

While the context vector has access to the entire input sequence, we don’t need to worry about forgetting. The alignment between the source and target is learned and controlled by the context vector. Essentially the context vector consumes three pieces of information:

- encoder hidden states;

- decoder hidden states;

- alignment between source and target.

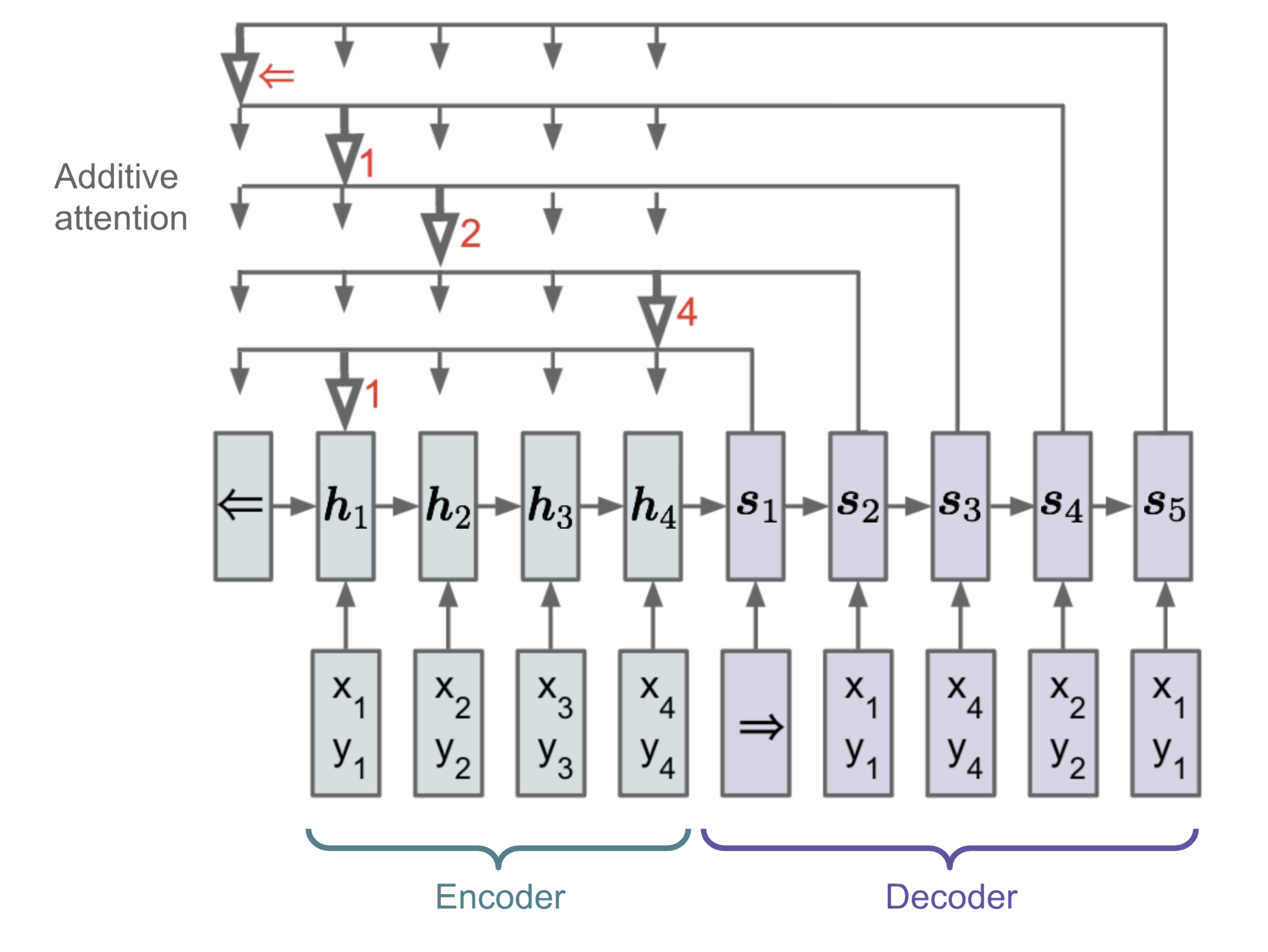

Fig. 4. The encoder-decoder model with additive attention mechanism in Bahdanau et al., 2015.

Definition

Now let’s define the attention mechanism introduced in NMT in a scientific way. Say, we have a source sequence \(\mathbf{x}\) of length \(n\) and try to output a target sequence \(\mathbf{y}\) of length \(m\):

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{x} &= [x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n] \\ \mathbf{y} &= [y_1, y_2, \dots, y_m] \end{aligned}\](Variables in bold indicate that they are vectors; same for everything else in this post.)

The encoder is a bidirectional RNN (or other recurrent network setting of your choice) with a forward hidden state \(\overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{h}}_i\) and a backward one \(\overleftarrow{\boldsymbol{h}}_i\). A simple concatenation of two represents the encoder state. The motivation is to include both the preceding and following words in the annotation of one word.

\[\boldsymbol{h}_i = [\overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{h}}_i^\top; \overleftarrow{\boldsymbol{h}}_i^\top]^\top, i=1,\dots,n\]The decoder network has hidden state \(\boldsymbol{s}_t=f(\boldsymbol{s}_{t-1}, y_{t-1}, \mathbf{c}_t)\) for the output word at position t, \(t=1,\dots,m\), where the context vector \(\mathbf{c}_t\) is a sum of hidden states of the input sequence, weighted by alignment scores:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{c}_t &= \sum_{i=1}^n \alpha_{t,i} \boldsymbol{h}_i & \small{\text{; Context vector for output }y_t}\\ \alpha_{t,i} &= \text{align}(y_t, x_i) & \small{\text{; How well two words }y_t\text{ and }x_i\text{ are aligned.}}\\ &= \frac{\exp(\text{score}(\boldsymbol{s}_{t-1}, \boldsymbol{h}_i))}{\sum_{i'=1}^n \exp(\text{score}(\boldsymbol{s}_{t-1}, \boldsymbol{h}_{i'}))} & \small{\text{; Softmax of some predefined alignment score.}}. \end{aligned}\]The alignment model assigns a score \(\alpha_{t,i}\) to the pair of input at position i and output at position t, \((y_t, x_i)\), based on how well they match. The set of \(\{\alpha_{t, i}\}\) are weights defining how much of each source hidden state should be considered for each output. In Bahdanau’s paper, the alignment score \(\alpha\) is parametrized by a feed-forward network with a single hidden layer and this network is jointly trained with other parts of the model. The score function is therefore in the following form, given that tanh is used as the non-linear activation function:

\[\text{score}(\boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{h}_i) = \mathbf{v}_a^\top \tanh(\mathbf{W}_a[\boldsymbol{s}_t; \boldsymbol{h}_i])\]where both \(\mathbf{v}_a\) and \(\mathbf{W}_a\) are weight matrices to be learned in the alignment model.

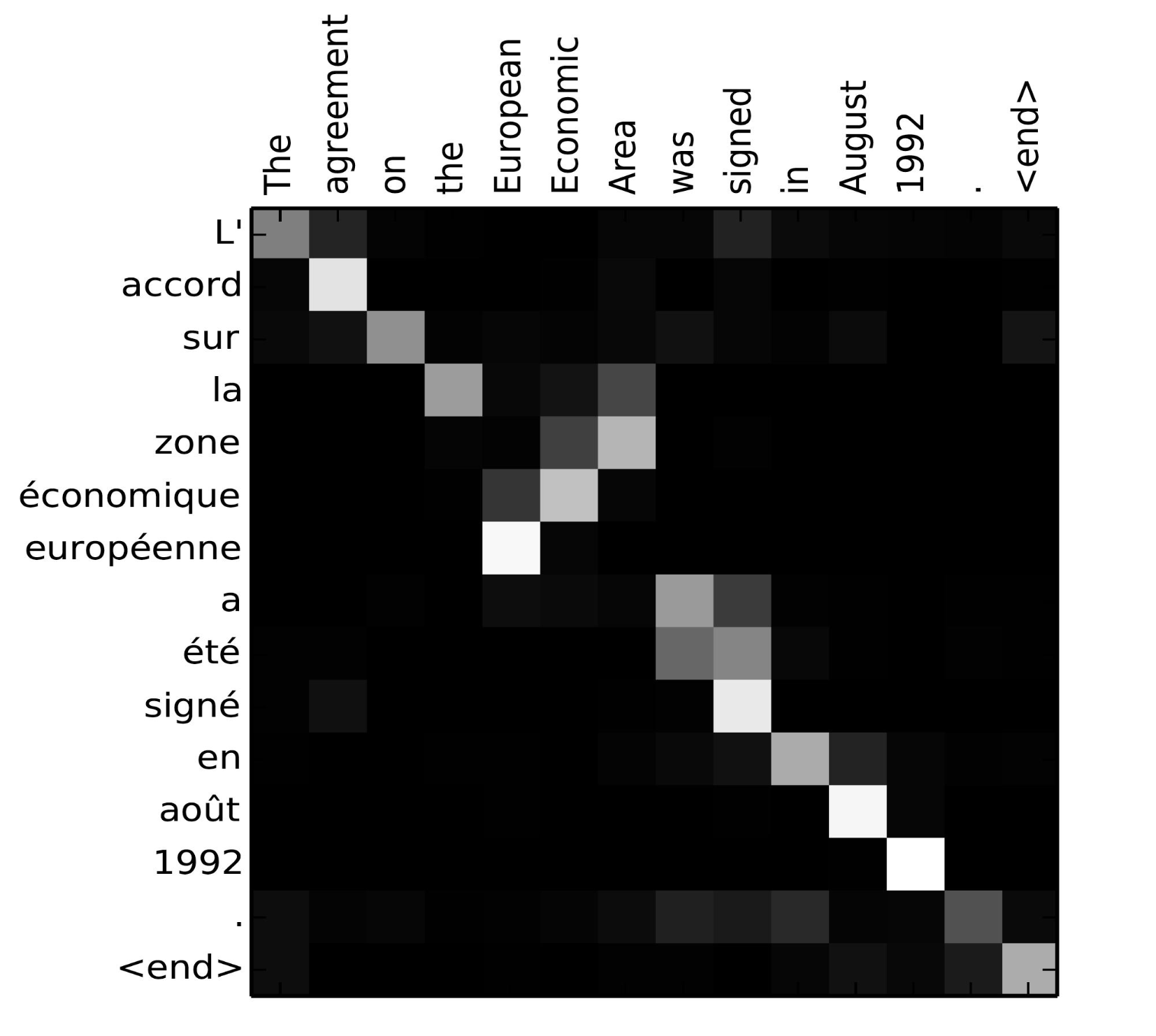

The matrix of alignment scores is a nice byproduct to explicitly show the correlation between source and target words.

Fig. 5. Alignment matrix of “L’accord sur l’Espace économique européen a été signé en août 1992” (French) and its English translation “The agreement on the European Economic Area was signed in August 1992”. (Image source: Fig 3 in Bahdanau et al., 2015)

Check out this nice tutorial by Tensorflow team for more implementation instructions.

A Family of Attention Mechanisms

With the help of the attention, the dependencies between source and target sequences are not restricted by the in-between distance anymore! Given the big improvement by attention in machine translation, it soon got extended into the computer vision field (Xu et al. 2015) and people started exploring various other forms of attention mechanisms (Luong, et al., 2015; Britz et al., 2017; Vaswani, et al., 2017).

Summary

Below is a summary table of several popular attention mechanisms and corresponding alignment score functions:

| Name | Alignment score function | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Content-base attention | \[\text{score}(\boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{h}_i) = \text{cosine}[\boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{h}_i]\] | Graves2014 |

| Additive(*) | \[\text{score}(\boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{h}_i) = \mathbf{v}_a^\top \tanh(\mathbf{W}_a[\boldsymbol{s}_t; \boldsymbol{h}_i])\] | Bahdanau2015 |

| Location-Base | \(\alpha_{t,i} = \text{softmax}(\mathbf{W}_a \boldsymbol{s}_t)\) Note: This simplifies the softmax alignment to only depend on the target position. |

Luong2015 |

| General | \(\text{score}(\boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{h}_i) = \boldsymbol{s}_t^\top\mathbf{W}_a\boldsymbol{h}_i\) where \(\mathbf{W}_a\) is a trainable weight matrix in the attention layer. |

Luong2015 |

| Dot-Product | \[\text{score}(\boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{h}_i) = \boldsymbol{s}_t^\top\boldsymbol{h}_i\] | Luong2015 |

| Scaled Dot-Product(^) | \(\text{score}(\boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{h}_i) = \frac{\boldsymbol{s}_t^\top\boldsymbol{h}_i}{\sqrt{n}}\) Note: very similar to the dot-product attention except for a scaling factor; where n is the dimension of the source hidden state. |

Vaswani2017 |

(*) Referred to as “concat” in Luong, et al., 2015 and as “additive attention” in Vaswani, et al., 2017.

(^) It adds a scaling factor \(1/\sqrt{n}\), motivated by the concern when the input is large, the softmax function may have an extremely small gradient, hard for efficient learning.

Here are a summary of broader categories of attention mechanisms:

| Name | Definition | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Attention(&) | Relating different positions of the same input sequence. Theoretically the self-attention can adopt any score functions above, but just replace the target sequence with the same input sequence. | Cheng2016 |

| Global/Soft | Attending to the entire input state space. | Xu2015 |

| Local/Hard | Attending to the part of input state space; i.e. a patch of the input image. | Xu2015; Luong2015 |

(&) Also, referred to as “intra-attention” in Cheng et al., 2016 and some other papers.

Self-Attention

Self-attention, also known as intra-attention, is an attention mechanism relating different positions of a single sequence in order to compute a representation of the same sequence. It has been shown to be very useful in machine reading, abstractive summarization, or image description generation.

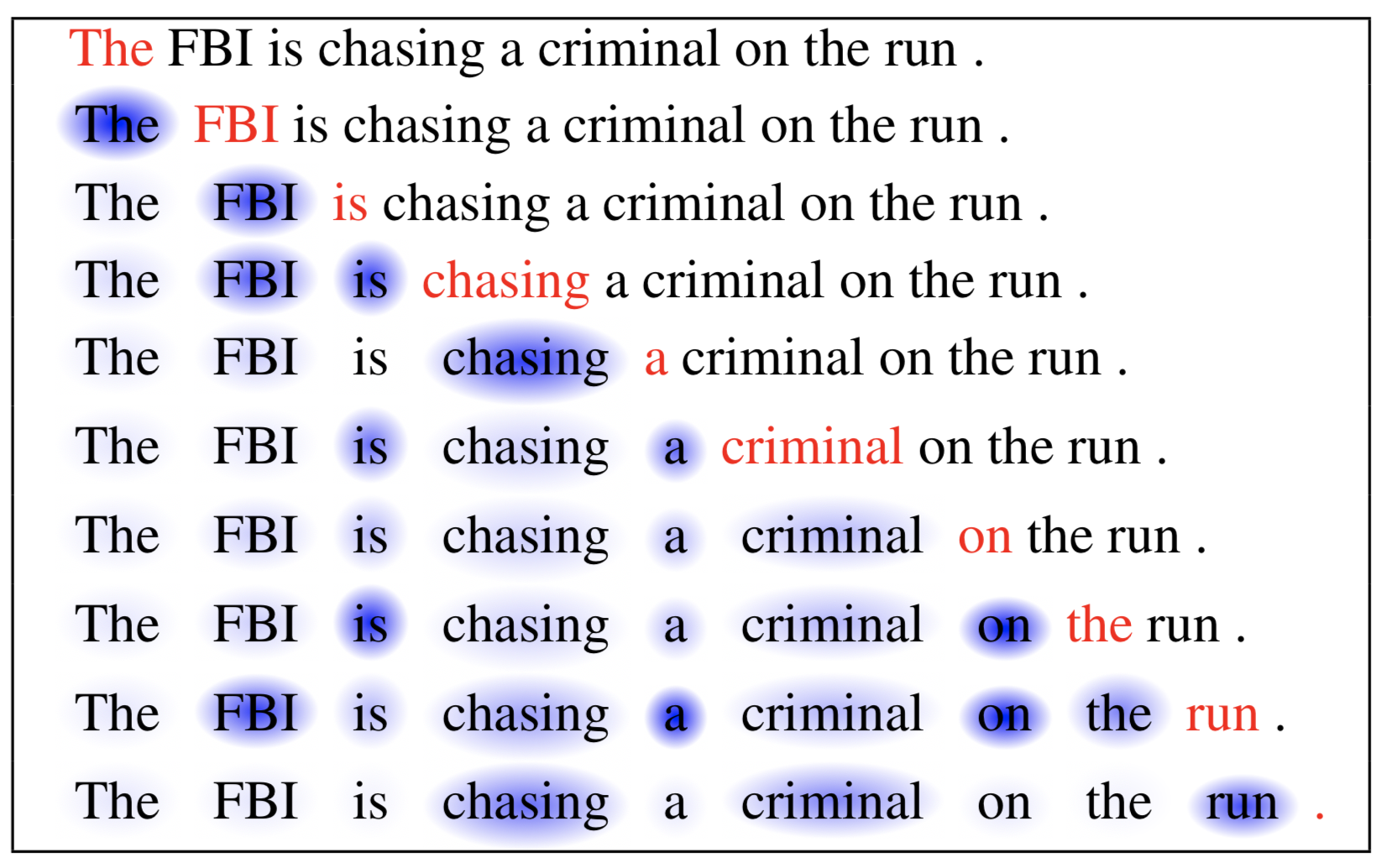

The long short-term memory network paper used self-attention to do machine reading. In the example below, the self-attention mechanism enables us to learn the correlation between the current words and the previous part of the sentence.

Fig. 6. The current word is in red and the size of the blue shade indicates the activation level. (Image source: Cheng et al., 2016)

Soft vs Hard Attention

In the show, attend and tell paper, attention mechanism is applied to images to generate captions. The image is first encoded by a CNN to extract features. Then a LSTM decoder consumes the convolution features to produce descriptive words one by one, where the weights are learned through attention. The visualization of the attention weights clearly demonstrates which regions of the image the model is paying attention to so as to output a certain word.

Fig. 7. “A woman is throwing a frisbee in a park.” (Image source: Fig. 6(b) in Xu et al. 2015)

This paper first proposed the distinction between “soft” vs “hard” attention, based on whether the attention has access to the entire image or only a patch:

-

Soft Attention: the alignment weights are learned and placed “softly” over all patches in the source image; essentially the same type of attention as in Bahdanau et al., 2015.

- Pro: the model is smooth and differentiable.

- Con: expensive when the source input is large.

-

Hard Attention: only selects one patch of the image to attend to at a time.

- Pro: less calculation at the inference time.

- Con: the model is non-differentiable and requires more complicated techniques such as variance reduction or reinforcement learning to train. (Luong, et al., 2015)

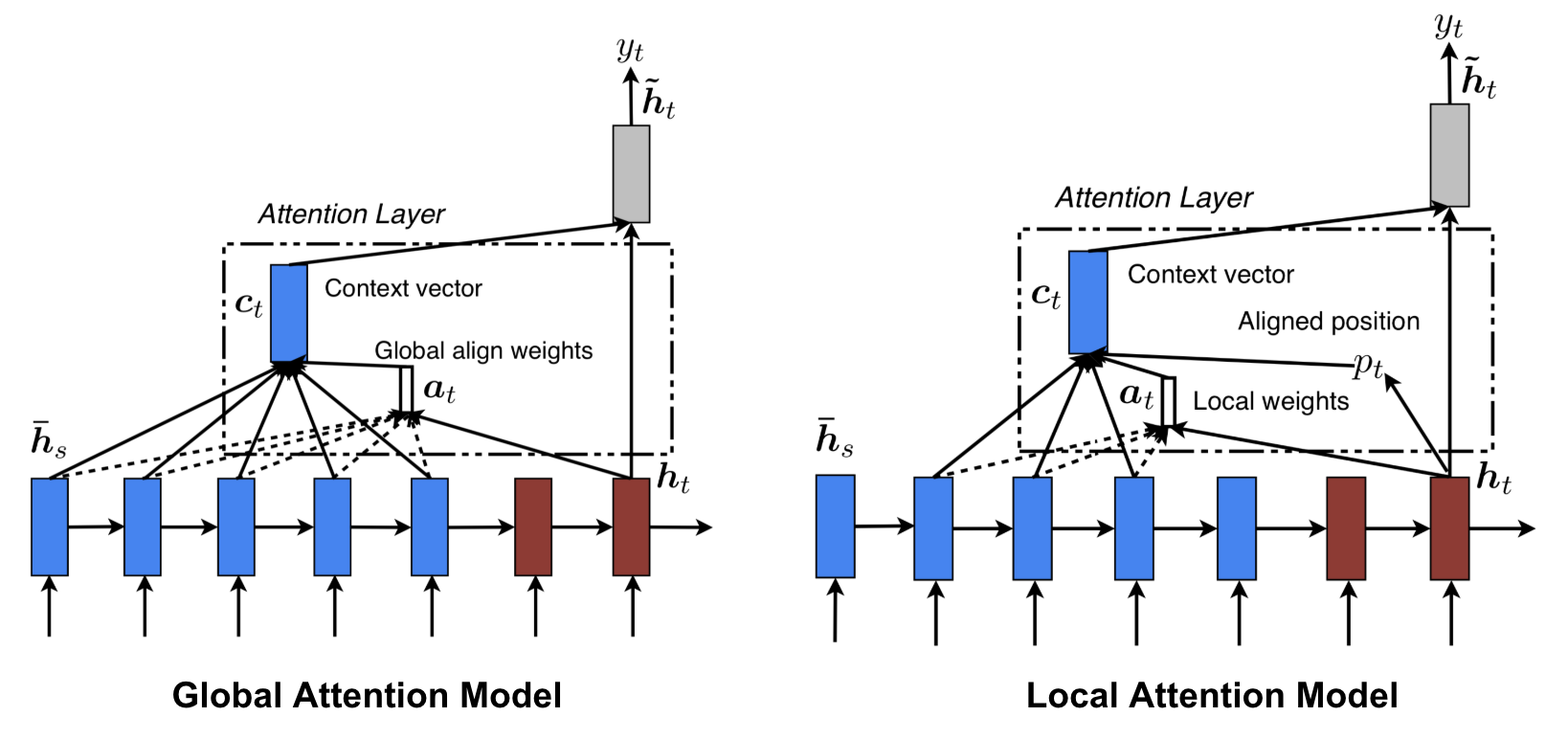

Global vs Local Attention

Luong, et al., 2015 proposed the “global” and “local” attention. The global attention is similar to the soft attention, while the local one is an interesting blend between hard and soft, an improvement over the hard attention to make it differentiable: the model first predicts a single aligned position for the current target word and a window centered around the source position is then used to compute a context vector.

Fig. 8. Global vs local attention (Image source: Fig 2 & 3 in Luong, et al., 2015)

Neural Turing Machines

Alan Turing in 1936 proposed a minimalistic model of computation. It is composed of a infinitely long tape and a head to interact with the tape. The tape has countless cells on it, each filled with a symbol: 0, 1 or blank (“ “). The operation head can read symbols, edit symbols and move left/right on the tape. Theoretically a Turing machine can simulate any computer algorithm, irrespective of how complex or expensive the procedure might be. The infinite memory gives a Turing machine an edge to be mathematically limitless. However, infinite memory is not feasible in real modern computers and then we only consider Turing machine as a mathematical model of computation.

Fig. 9. How a Turing machine looks like: a tape + a head that handles the tape. (Image source: http://aturingmachine.com/)

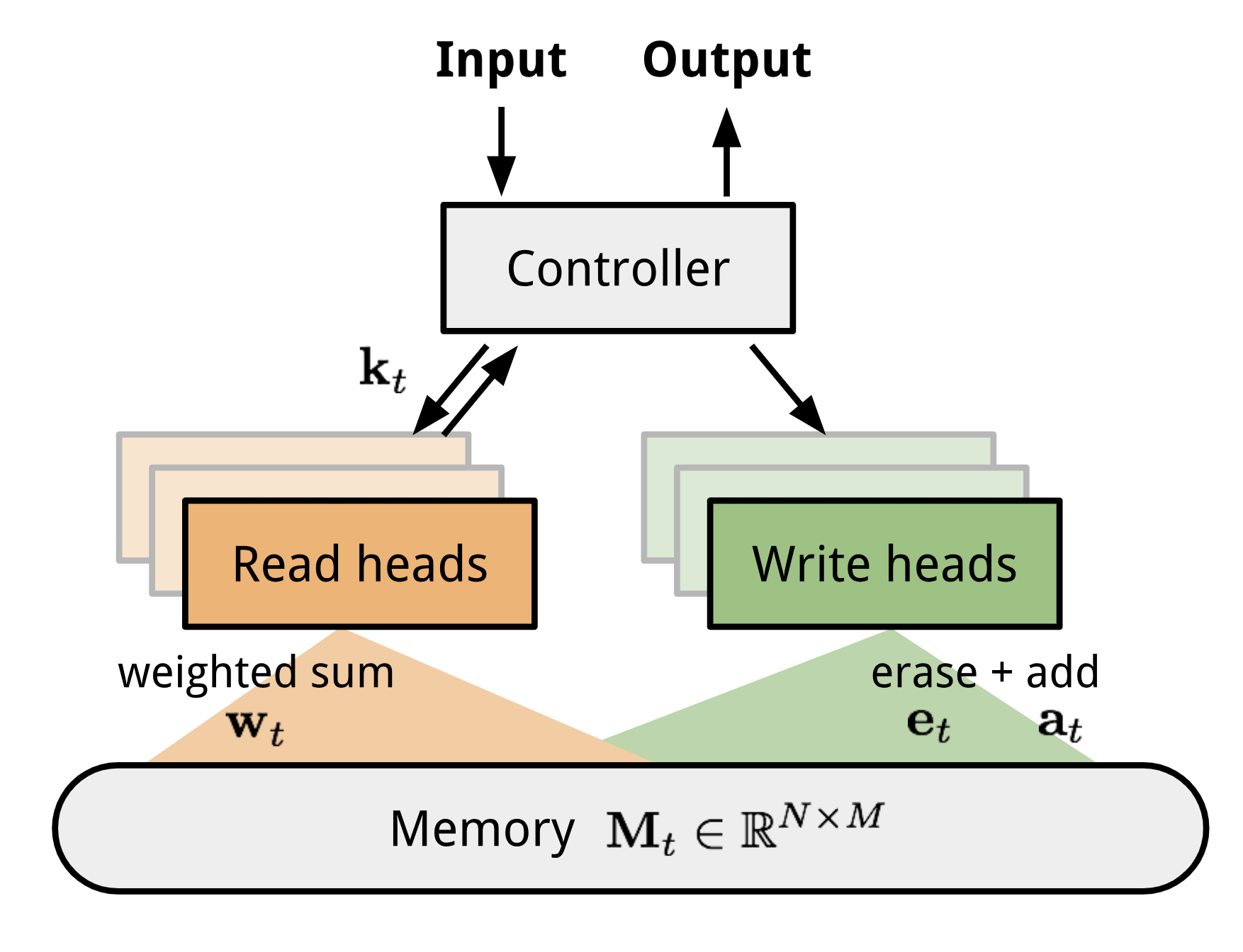

Neural Turing Machine (NTM, Graves, Wayne & Danihelka, 2014) is a model architecture for coupling a neural network with external memory storage. The memory mimics the Turing machine tape and the neural network controls the operation heads to read from or write to the tape. However, the memory in NTM is finite, and thus it probably looks more like a “Neural von Neumann Machine”.

NTM contains two major components, a controller neural network and a memory bank. Controller: is in charge of executing operations on the memory. It can be any type of neural network, feed-forward or recurrent. Memory: stores processed information. It is a matrix of size \(N \times M\), containing N vector rows and each has \(M\) dimensions.

In one update iteration, the controller processes the input and interacts with the memory bank accordingly to generate output. The interaction is handled by a set of parallel read and write heads. Both read and write operations are “blurry” by softly attending to all the memory addresses.

Fig 10. Neural Turing Machine Architecture.

Reading and Writing

When reading from the memory at time t, an attention vector of size \(N\), \(\mathbf{w}_t\) controls how much attention to assign to different memory locations (matrix rows). The read vector \(\mathbf{r}_t\) is a sum weighted by attention intensity:

\[\mathbf{r}_t = \sum_{i=1}^N w_t(i)\mathbf{M}_t(i)\text{, where }\sum_{i=1}^N w_t(i)=1, \forall i: 0 \leq w_t(i) \leq 1\]where \(w_t(i)\) is the \(i\)-th element in \(\mathbf{w}_t\) and \(\mathbf{M}_t(i)\) is the \(i\)-th row vector in the memory.

When writing into the memory at time t, as inspired by the input and forget gates in LSTM, a write head first wipes off some old content according to an erase vector \(\mathbf{e}_t\) and then adds new information by an add vector \(\mathbf{a}_t\).

\[\begin{aligned} \tilde{\mathbf{M}}_t(i) &= \mathbf{M}_{t-1}(i) [\mathbf{1} - w_t(i)\mathbf{e}_t] &\scriptstyle{\text{; erase}}\\ \mathbf{M}_t(i) &= \tilde{\mathbf{M}}_t(i) + w_t(i) \mathbf{a}_t &\scriptstyle{\text{; add}} \end{aligned}\]Attention Mechanisms

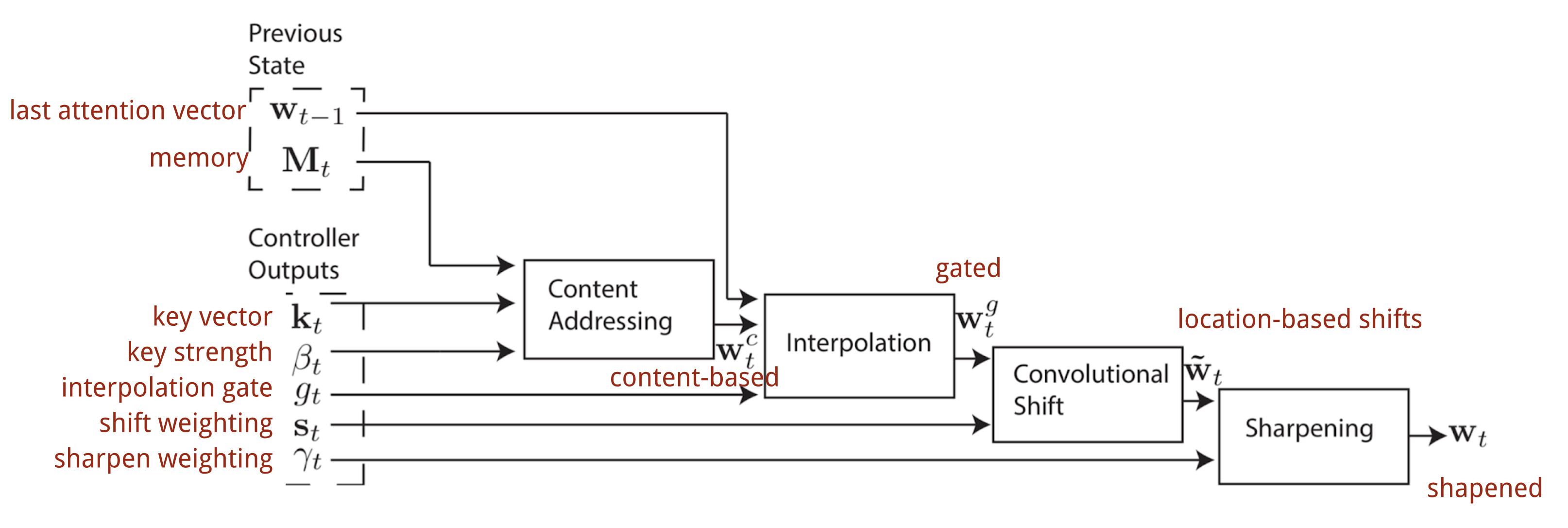

In Neural Turing Machine, how to generate the attention distribution \(\mathbf{w}_t\) depends on the addressing mechanisms: NTM uses a mixture of content-based and location-based addressings.

Content-based addressing

The content-addressing creates attention vectors based on the similarity between the key vector \(\mathbf{k}_t\) extracted by the controller from the input and memory rows. The content-based attention scores are computed as cosine similarity and then normalized by softmax. In addition, NTM adds a strength multiplier \(\beta_t\) to amplify or attenuate the focus of the distribution.

\[w_t^c(i) = \text{softmax}(\beta_t \cdot \text{cosine}[\mathbf{k}_t, \mathbf{M}_t(i)]) = \frac{\exp(\beta_t \frac{\mathbf{k}_t \cdot \mathbf{M}_t(i)}{\|\mathbf{k}_t\| \cdot \|\mathbf{M}_t(i)\|})}{\sum_{j=1}^N \exp(\beta_t \frac{\mathbf{k}_t \cdot \mathbf{M}_t(j)}{\|\mathbf{k}_t\| \cdot \|\mathbf{M}_t(j)\|})}\]Interpolation

Then an interpolation gate scalar \(g_t\) is used to blend the newly generated content-based attention vector with the attention weights in the last time step:

\[\mathbf{w}_t^g = g_t \mathbf{w}_t^c + (1 - g_t) \mathbf{w}_{t-1}\]Location-based addressing

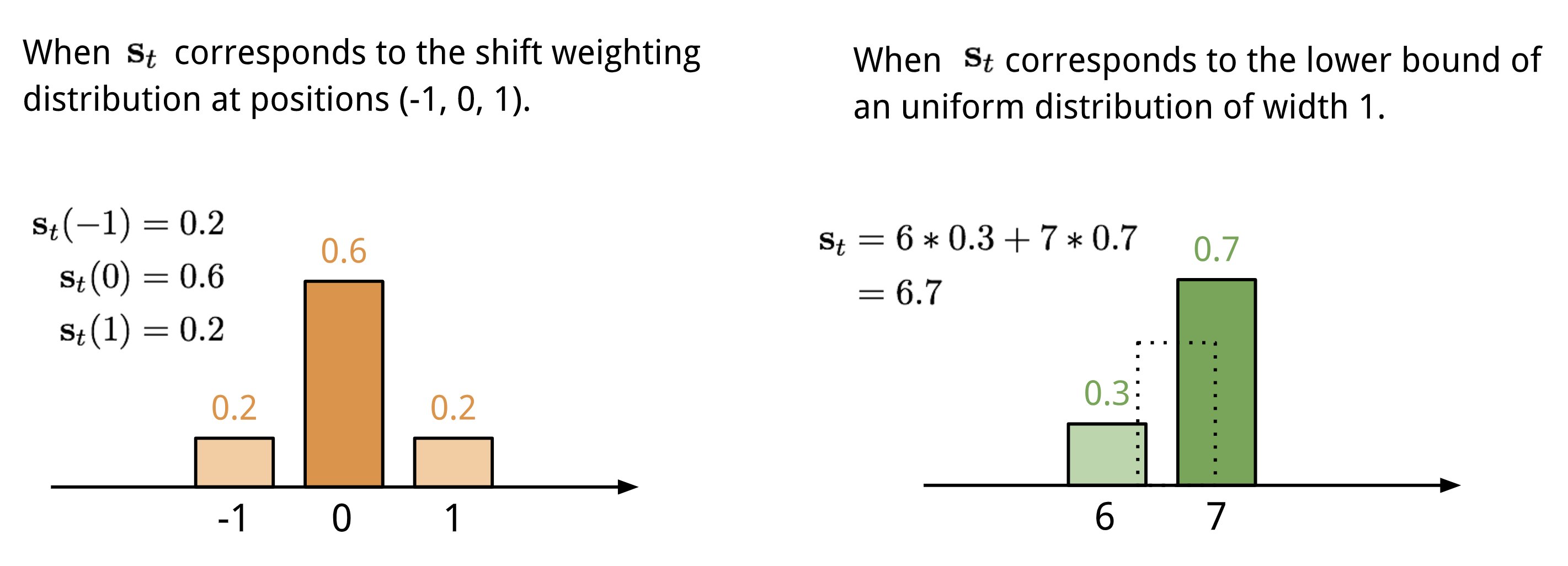

The location-based addressing sums up the values at different positions in the attention vector, weighted by a weighting distribution over allowable integer shifts. It is equivalent to a 1-d convolution with a kernel \(\mathbf{s}_t(.)\), a function of the position offset. There are multiple ways to define this distribution. See Fig. 11. for inspiration.

Fig. 11. Two ways to represent the shift weighting distribution \(\mathbf{s}_t\).

Finally the attention distribution is enhanced by a sharpening scalar \(\gamma_t \geq 1\).

\[\begin{aligned} \tilde{w}_t(i) &= \sum_{j=1}^N w_t^g(j) s_t(i-j) & \scriptstyle{\text{; circular convolution}}\\ w_t(i) &= \frac{\tilde{w}_t(i)^{\gamma_t}}{\sum_{j=1}^N \tilde{w}_t(j)^{\gamma_t}} & \scriptstyle{\text{; sharpen}} \end{aligned}\]The complete process of generating the attention vector \(\mathbf{w}_t\) at time step t is illustrated in Fig. 12. All the parameters produced by the controller are unique for each head. If there are multiple read and write heads in parallel, the controller would output multiple sets.

Fig. 12. Flow diagram of the addressing mechanisms in Neural Turing Machine. (Image source: Graves, Wayne & Danihelka, 2014)

Pointer Network

In problems like sorting or travelling salesman, both input and output are sequential data. Unfortunately, they cannot be easily solved by classic seq-2-seq or NMT models, given that the discrete categories of output elements are not determined in advance, but depends on the variable input size. The Pointer Net (Ptr-Net; Vinyals, et al. 2015) is proposed to resolve this type of problems: When the output elements correspond to positions in an input sequence. Rather than using attention to blend hidden units of an encoder into a context vector (See Fig. 8), the Pointer Net applies attention over the input elements to pick one as the output at each decoder step.

Fig. 13. The architecture of a Pointer Network model. (Image source: Vinyals, et al. 2015)

The Ptr-Net outputs a sequence of integer indices, \(\boldsymbol{c} = (c_1, \dots, c_m)\) given a sequence of input vectors \(\boldsymbol{x} = (x_1, \dots, x_n)\) and \(1 \leq c_i \leq n\). The model still embraces an encoder-decoder framework. The encoder and decoder hidden states are denoted as \((\boldsymbol{h}_1, \dots, \boldsymbol{h}_n)\) and \((\boldsymbol{s}_1, \dots, \boldsymbol{s}_m)\), respectively. Note that \(\mathbf{s}_i\) is the output gate after cell activation in the decoder. The Ptr-Net applies additive attention between states and then normalizes it by softmax to model the output conditional probability:

\[\begin{aligned} y_i &= p(c_i \vert c_1, \dots, c_{i-1}, \boldsymbol{x}) \\ &= \text{softmax}(\text{score}(\boldsymbol{s}_t; \boldsymbol{h}_i)) = \text{softmax}(\mathbf{v}_a^\top \tanh(\mathbf{W}_a[\boldsymbol{s}_t; \boldsymbol{h}_i])) \end{aligned}\]The attention mechanism is simplified, as Ptr-Net does not blend the encoder states into the output with attention weights. In this way, the output only responds to the positions but not the input content.

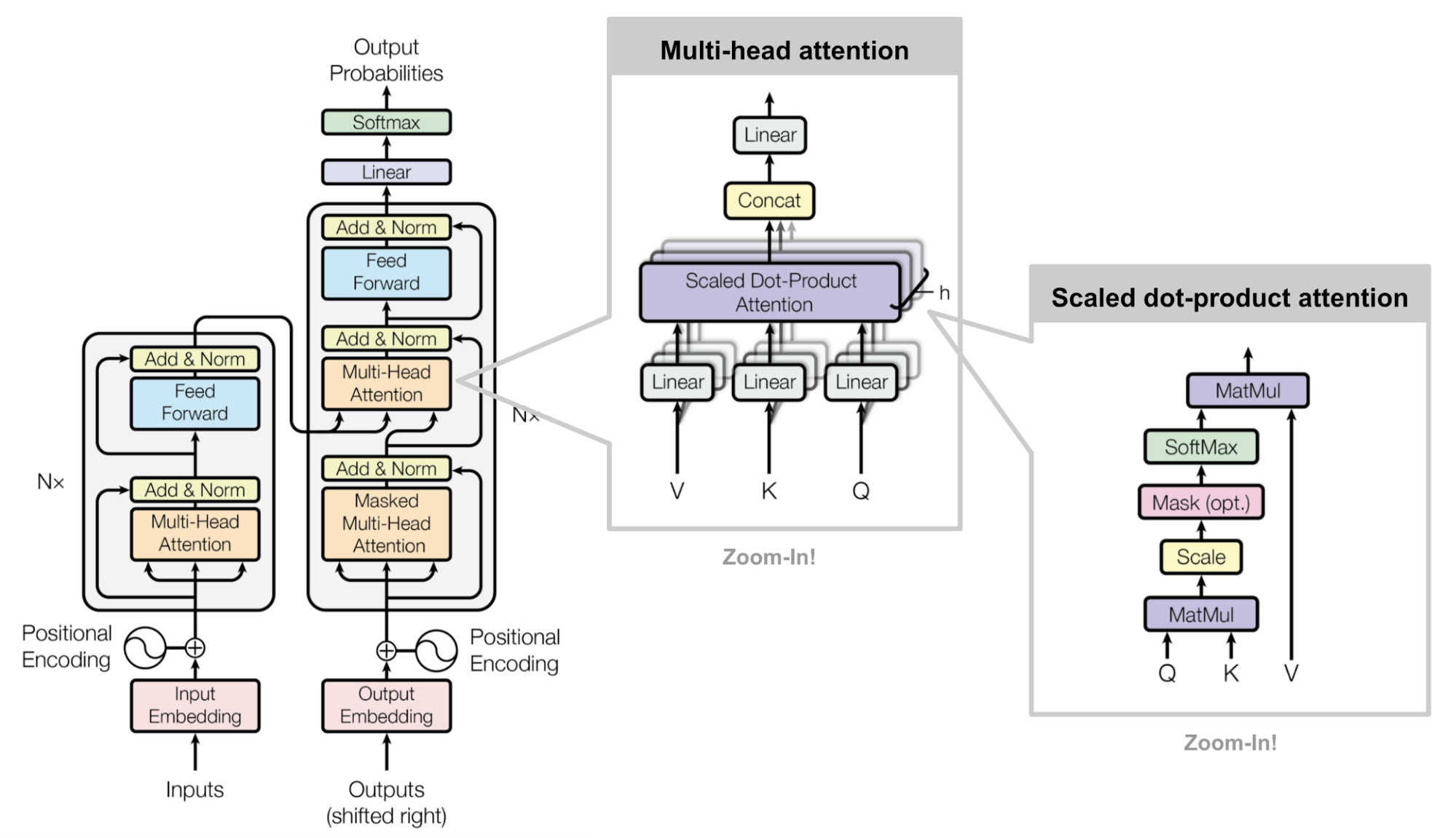

Transformer

“Attention is All you Need” (Vaswani, et al., 2017), without a doubt, is one of the most impactful and interesting paper in 2017. It presented a lot of improvements to the soft attention and make it possible to do seq2seq modeling without recurrent network units. The proposed “transformer” model is entirely built on the self-attention mechanisms without using sequence-aligned recurrent architecture.

The secret recipe is carried in its model architecture.

Key, Value and Query

The major component in the transformer is the unit of multi-head self-attention mechanism. The transformer views the encoded representation of the input as a set of key-value pairs, \((\mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V})\), both of dimension \(n\) (input sequence length); in the context of NMT, both the keys and values are the encoder hidden states. In the decoder, the previous output is compressed into a query (\(\mathbf{Q}\) of dimension \(m\)) and the next output is produced by mapping this query and the set of keys and values.

The transformer adopts the scaled dot-product attention: the output is a weighted sum of the values, where the weight assigned to each value is determined by the dot-product of the query with all the keys:

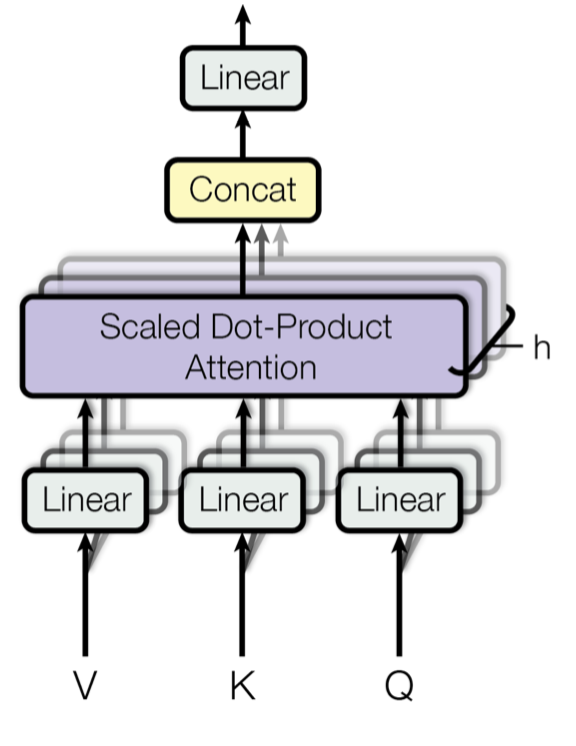

\[\text{Attention}(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}) = \text{softmax}(\frac{\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^\top}{\sqrt{n}})\mathbf{V}\]Multi-Head Self-Attention

Fig. 14. Multi-head scaled dot-product attention mechanism. (Image source: Fig 2 in Vaswani, et al., 2017)

Rather than only computing the attention once, the multi-head mechanism runs through the scaled dot-product attention multiple times in parallel. The independent attention outputs are simply concatenated and linearly transformed into the expected dimensions. I assume the motivation is because ensembling always helps? ;) According to the paper, “multi-head attention allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces at different positions. With a single attention head, averaging inhibits this.”

\[\begin{aligned} \text{MultiHead}(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}) &= [\text{head}_1; \dots; \text{head}_h]\mathbf{W}^O \\ \text{where head}_i &= \text{Attention}(\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{W}^Q_i, \mathbf{K}\mathbf{W}^K_i, \mathbf{V}\mathbf{W}^V_i) \end{aligned}\]where \(\mathbf{W}^Q_i\), \(\mathbf{W}^K_i\), \(\mathbf{W}^V_i\), and \(\mathbf{W}^O\) are parameter matrices to be learned.

Encoder

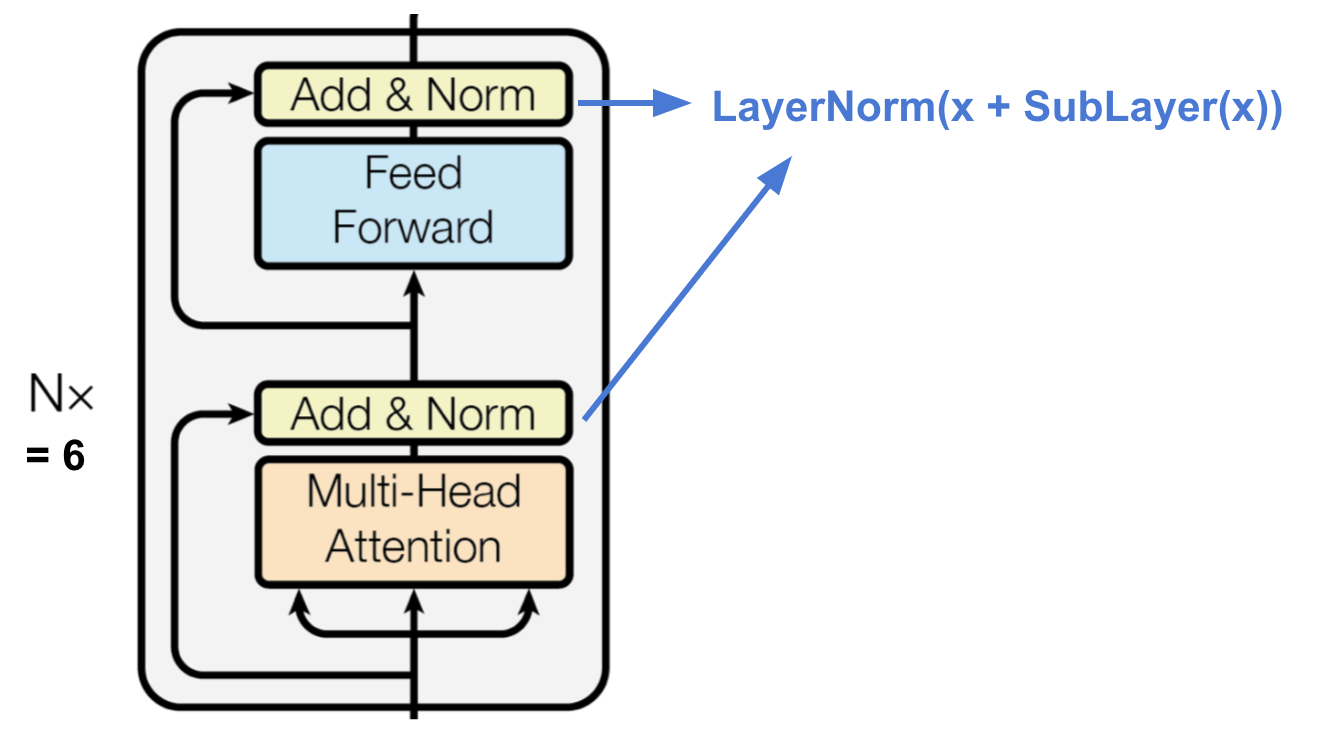

Fig. 15. The transformer’s encoder. (Image source: Vaswani, et al., 2017)

The encoder generates an attention-based representation with capability to locate a specific piece of information from a potentially infinitely-large context.

- A stack of N=6 identical layers.

- Each layer has a multi-head self-attention layer and a simple position-wise fully connected feed-forward network.

- Each sub-layer adopts a residual connection and a layer normalization. All the sub-layers output data of the same dimension \(d_\text{model} = 512\).

Decoder

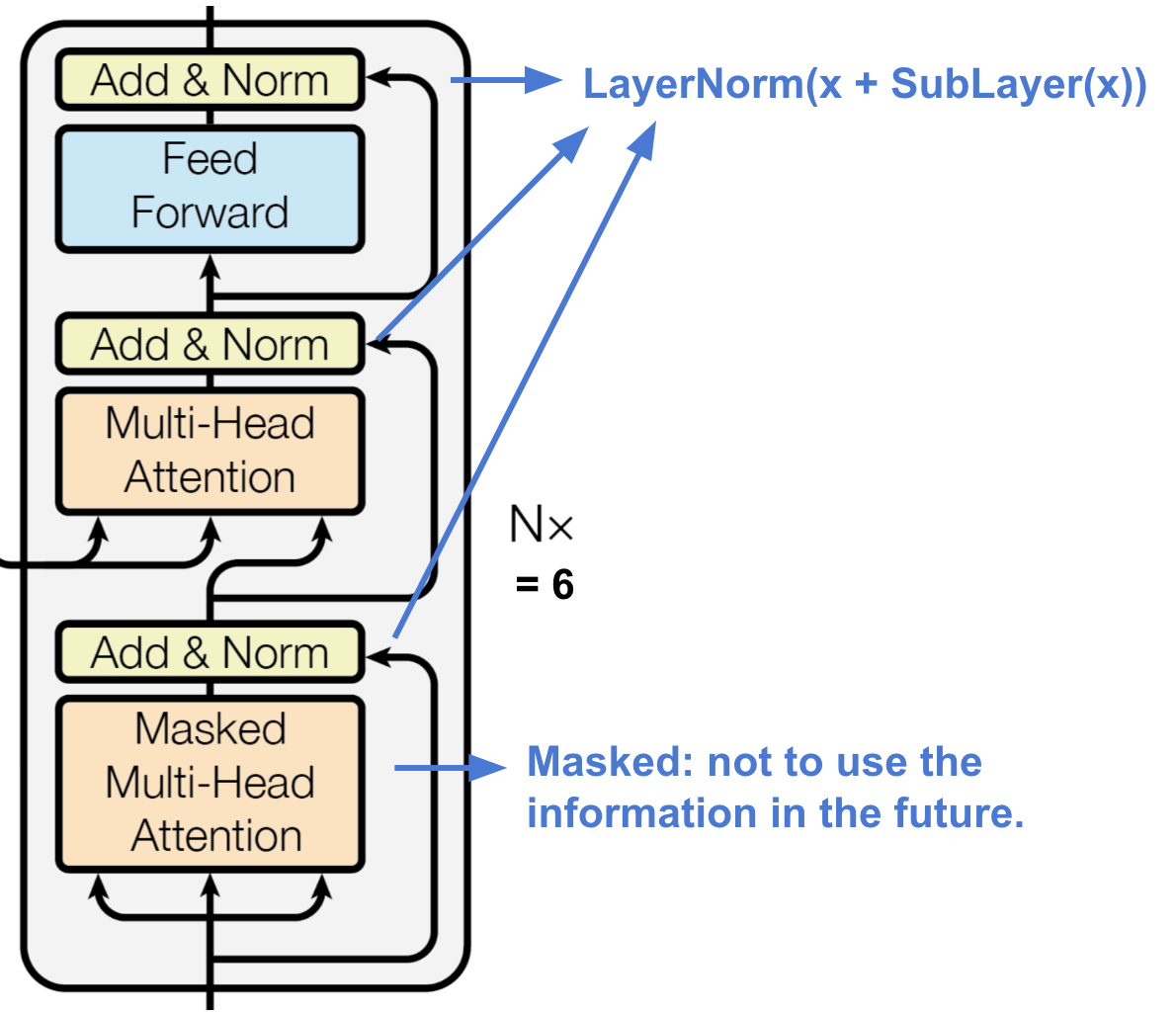

Fig. 16. The transformer’s decoder. (Image source: Vaswani, et al., 2017)

The decoder is able to retrieval from the encoded representation.

- A stack of N = 6 identical layers

- Each layer has two sub-layers of multi-head attention mechanisms and one sub-layer of fully-connected feed-forward network.

- Similar to the encoder, each sub-layer adopts a residual connection and a layer normalization.

- The first multi-head attention sub-layer is modified to prevent positions from attending to subsequent positions, as we don’t want to look into the future of the target sequence when predicting the current position.

Full Architecture

Finally here is the complete view of the transformer’s architecture:

- Both the source and target sequences first go through embedding layers to produce data of the same dimension \(d_\text{model} =512\).

- To preserve the position information, a sinusoid-wave-based positional encoding is applied and summed with the embedding output.

- A softmax and linear layer are added to the final decoder output.

Fig. 17. The full model architecture of the transformer. (Image source: Fig 1 & 2 in Vaswani, et al., 2017.)

Try to implement the transformer model is an interesting experience, here is mine: lilianweng/transformer-tensorflow. Read the comments in the code if you are interested.

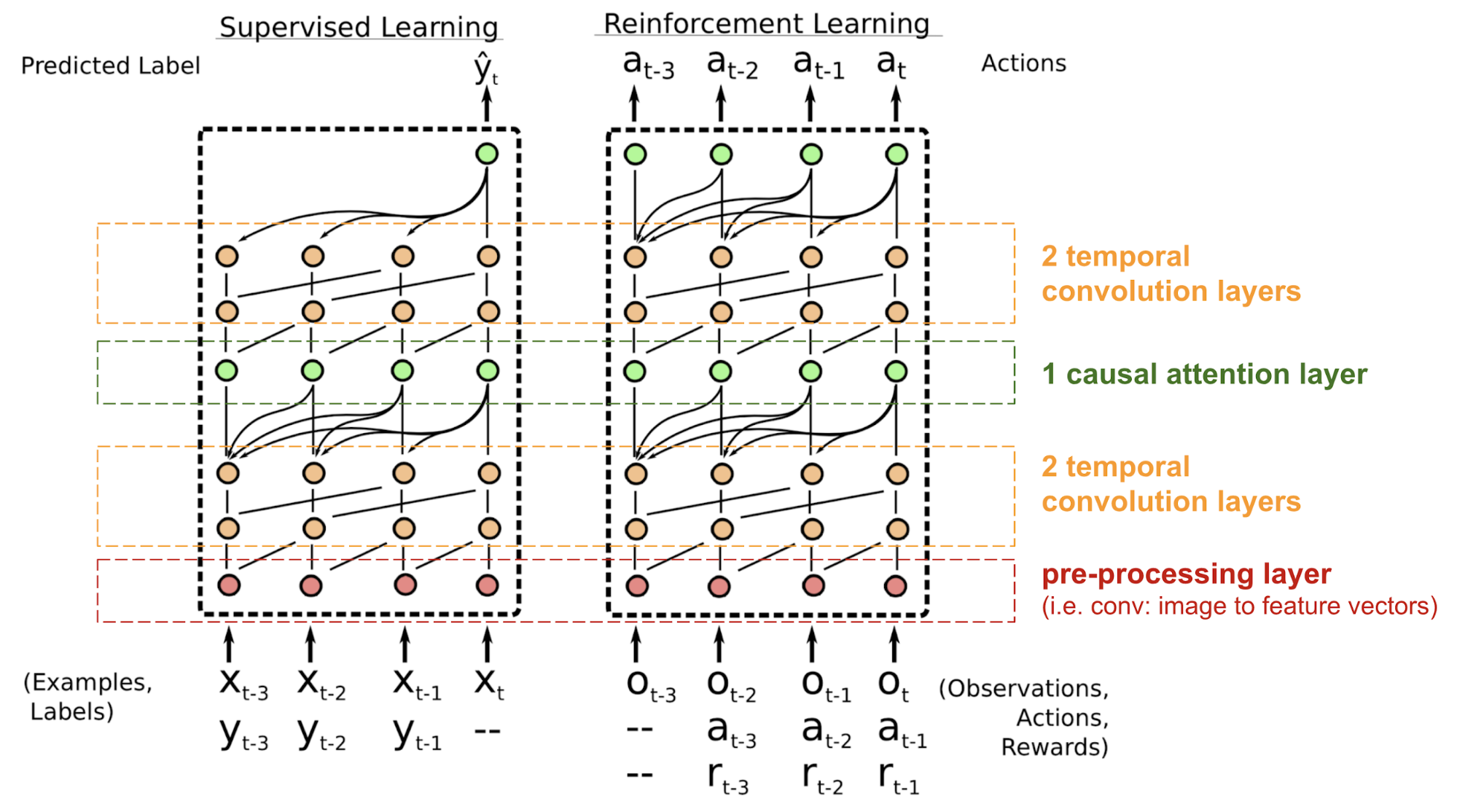

SNAIL

The transformer has no recurrent or convolutional structure, even with the positional encoding added to the embedding vector, the sequential order is only weakly incorporated. For problems sensitive to the positional dependency like reinforcement learning, this can be a big problem.

The Simple Neural Attention Meta-Learner (SNAIL) (Mishra et al., 2017) was developed partially to resolve the problem with positioning in the transformer model by combining the self-attention mechanism in transformer with temporal convolutions. It has been demonstrated to be good at both supervised learning and reinforcement learning tasks.

Fig. 18. SNAIL model architecture (Image source: Mishra et al., 2017)

SNAIL was born in the field of meta-learning, which is another big topic worthy of a post by itself. But in simple words, the meta-learning model is expected to be generalizable to novel, unseen tasks in the similar distribution. Read this nice introduction if interested.

Self-Attention GAN

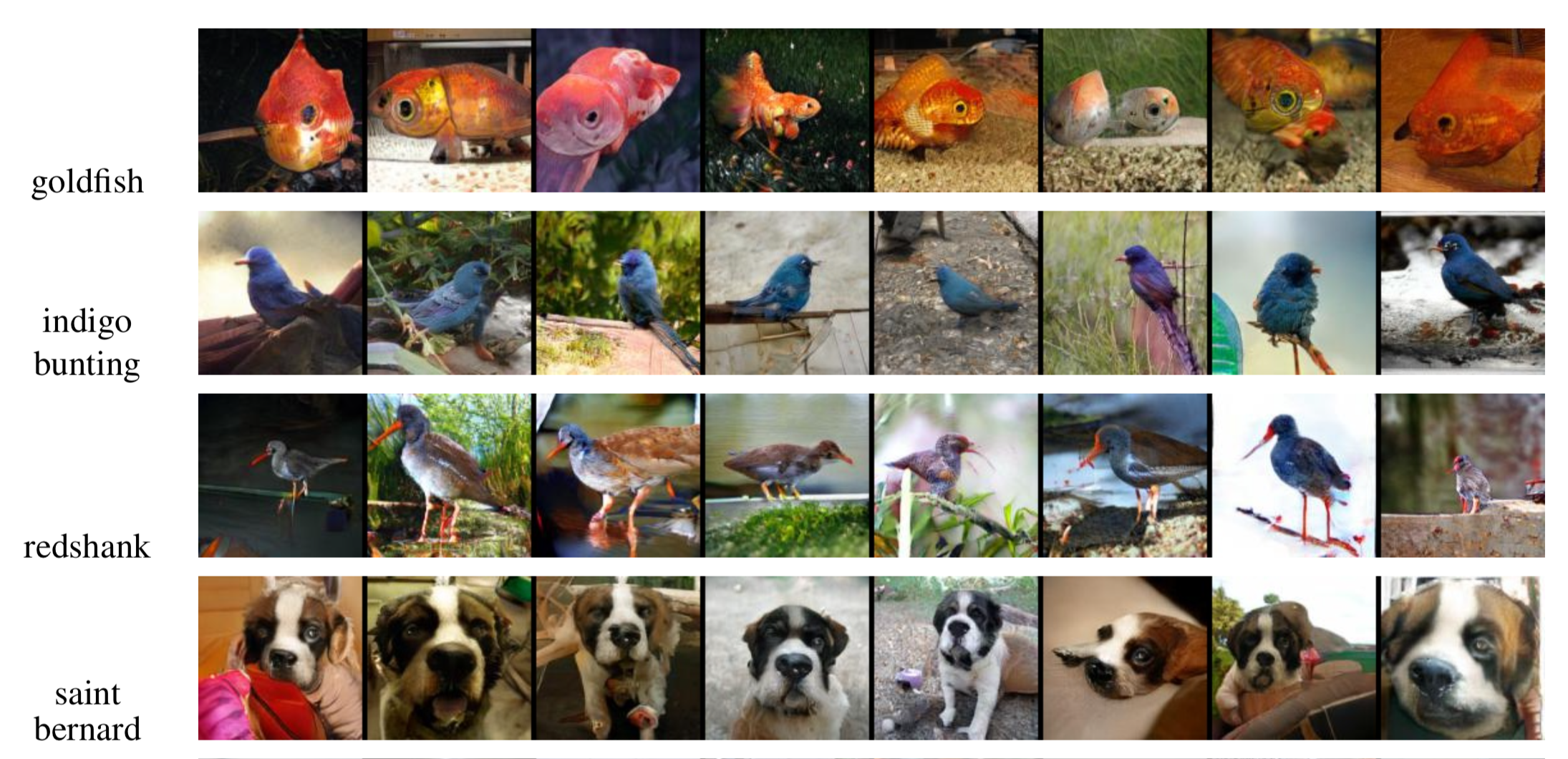

Self-Attention GAN (SAGAN; Zhang et al., 2018) adds self-attention layers into GAN to enable both the generator and the discriminator to better model relationships between spatial regions.

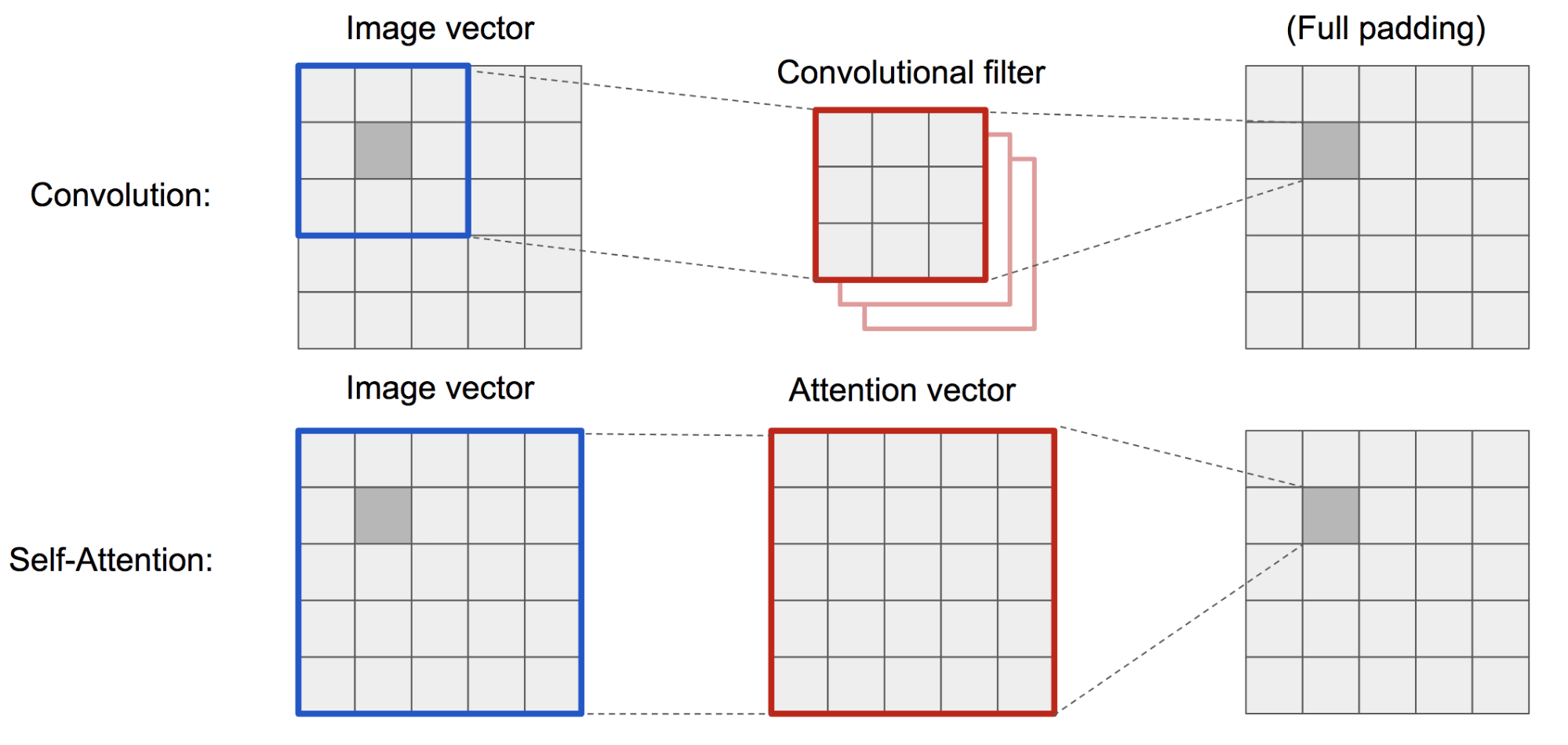

The classic DCGAN (Deep Convolutional GAN) represents both discriminator and generator as multi-layer convolutional networks. However, the representation capacity of the network is restrained by the filter size, as the feature of one pixel is limited to a small local region. In order to connect regions far apart, the features have to be dilute through layers of convolutional operations and the dependencies are not guaranteed to be maintained.

As the (soft) self-attention in the vision context is designed to explicitly learn the relationship between one pixel and all other positions, even regions far apart, it can easily capture global dependencies. Hence GAN equipped with self-attention is expected to handle details better, hooray!

Fig. 19. Convolution operation and self-attention have access to regions of very different sizes.

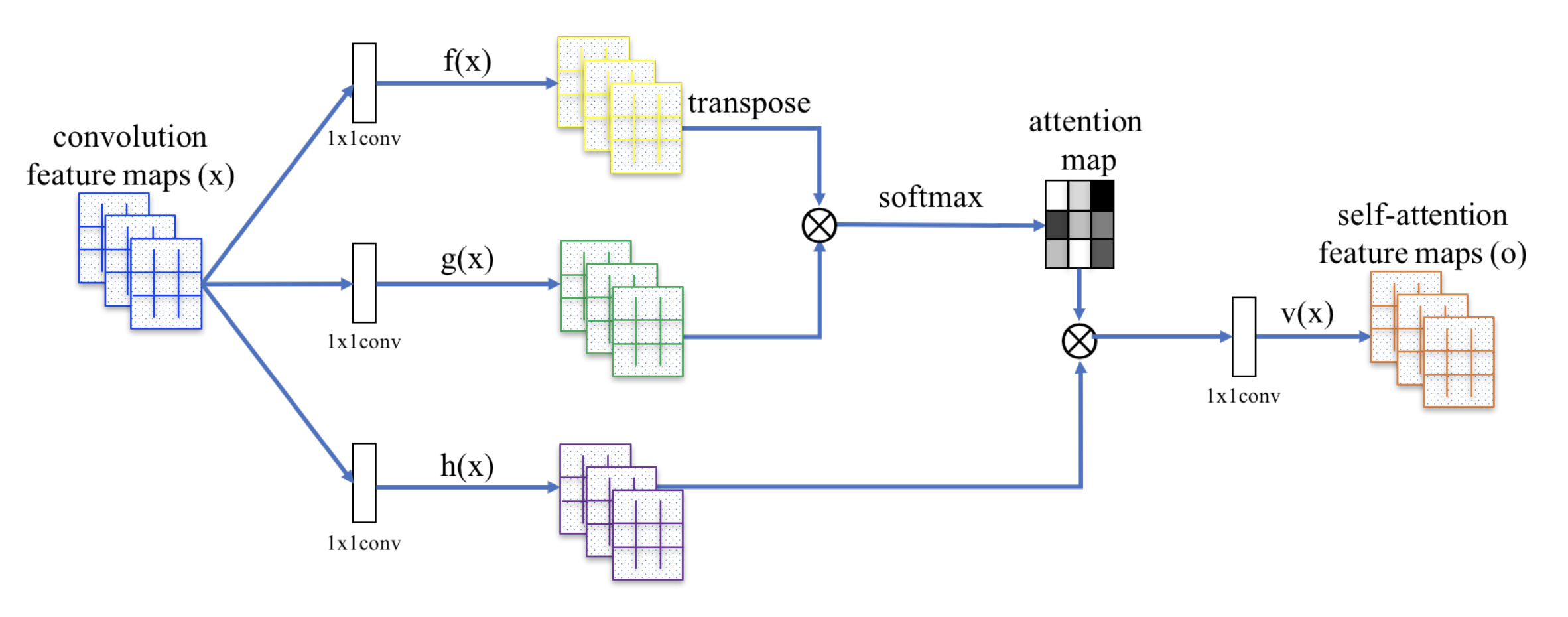

The SAGAN adopts the non-local neural network to apply the attention computation. The convolutional image feature maps \(\mathbf{x}\) is branched out into three copies, corresponding to the concepts of key, value, and query in the transformer:

- Key: \(f(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{W}_f \mathbf{x}\)

- Query: \(g(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{W}_g \mathbf{x}\)

- Value: \(h(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{W}_h \mathbf{x}\)

Then we apply the dot-product attention to output the self-attention feature maps:

\[\begin{aligned} \alpha_{i,j} &= \text{softmax}(f(\mathbf{x}_i)^\top g(\mathbf{x}_j)) \\ \mathbf{o}_j &= \mathbf{W}_v \Big( \sum_{i=1}^N \alpha_{i,j} h(\mathbf{x}_i) \Big) \end{aligned}\]

Fig. 20. The self-attention mechanism in SAGAN. (Image source: Fig. 2 in Zhang et al., 2018)

Note that \(\alpha_{i,j}\) is one entry in the attention map, indicating how much attention the model should pay to the \(i\)-th position when synthesizing the \(j\)-th location. \(\mathbf{W}_f\), \(\mathbf{W}_g\), and \(\mathbf{W}_h\) are all 1x1 convolution filters. If you feel that 1x1 conv sounds like a weird concept (i.e., isn’t it just to multiply the whole feature map with one number?), watch this short tutorial by Andrew Ng. The output \(\mathbf{o}_j\) is a column vector of the final output \(\mathbf{o}= (\mathbf{o}_1, \mathbf{o}_2, \dots, \mathbf{o}_j, \dots, \mathbf{o}_N)\).

Furthermore, the output of the attention layer is multiplied by a scale parameter and added back to the original input feature map:

\[\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{x}_i + \gamma \mathbf{o}_i\]While the scaling parameter \(\gamma\) is increased gradually from 0 during the training, the network is configured to first rely on the cues in the local regions and then gradually learn to assign more weight to the regions that are further away.

Fig. 21. 128×128 example images generated by SAGAN for different classes. (Image source: Partial Fig. 6 in Zhang et al., 2018)

Cited as:

@article{weng2018attention,

title = "Attention? Attention!",

author = "Weng, Lilian",

journal = "lilianweng.github.io/lil-log",

year = "2018",

url = "http://lilianweng.github.io/lil-log/2018/06/24/attention-attention.html"

}

References

[1] “Attention and Memory in Deep Learning and NLP.” - Jan 3, 2016 by Denny Britz

[2] “Neural Machine Translation (seq2seq) Tutorial”

[3] Dzmitry Bahdanau, Kyunghyun Cho, and Yoshua Bengio. “Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate.” ICLR 2015.

[4] Kelvin Xu, Jimmy Ba, Ryan Kiros, Kyunghyun Cho, Aaron Courville, Ruslan Salakhudinov, Rich Zemel, and Yoshua Bengio. “Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention.” ICML, 2015.

[5] Ilya Sutskever, Oriol Vinyals, and Quoc V. Le. “Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks.” NIPS 2014.

[6] Thang Luong, Hieu Pham, Christopher D. Manning. “Effective Approaches to Attention-based Neural Machine Translation.” EMNLP 2015.

[7] Denny Britz, Anna Goldie, Thang Luong, and Quoc Le. “Massive exploration of neural machine translation architectures.” ACL 2017.

[8] Ashish Vaswani, et al. “Attention is all you need.” NIPS 2017.

[9] Jianpeng Cheng, Li Dong, and Mirella Lapata. “Long short-term memory-networks for machine reading.” EMNLP 2016.

[10] Xiaolong Wang, et al. “Non-local Neural Networks.” CVPR 2018

[11] Han Zhang, Ian Goodfellow, Dimitris Metaxas, and Augustus Odena. “Self-Attention Generative Adversarial Networks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.08318 (2018).

[12] Nikhil Mishra, Mostafa Rohaninejad, Xi Chen, and Pieter Abbeel. “A simple neural attentive meta-learner.” ICLR 2018.

[13] “WaveNet: A Generative Model for Raw Audio” - Sep 8, 2016 by DeepMind.

[14] Oriol Vinyals, Meire Fortunato, and Navdeep Jaitly. “Pointer networks.” NIPS 2015.

[15] Alex Graves, Greg Wayne, and Ivo Danihelka. “Neural turing machines.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.5401 (2014).